Of all the diseases that the U.S. government announced today that it will no longer recommend vaccines against, rotavirus is by no means the deadliest. Not all children develop substantial symptoms; most of those who do experience a few days of fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, and then get better. In the early 1970s, when no rotavirus vaccines were available and most children could expect to be sickened with the virus at least once by the end of toddlerhood, Paul Offit considered it to be no big deal, relatively speaking. In this country especially, rotavirus “was an illness from which children recovered,” he told me.

That perception shifted abruptly during Offit’s pediatric residency training, when he saw hundreds of severe rotavirus cases admitted to the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh each year. Although plenty of children weathered the infection largely without bad symptoms, others vomited so profusely that they struggled to keep down the fluids they desperately needed. Offit can still recall the nine-month-old he treated in the late 1970s who was hospitalized after her mother had struggled to feed her sufficient fluids at home. The infant was so severely dehydrated that Offit and his colleagues couldn’t find a vein in which to insert an IV; as a last resort, they attempted to drill a needle into her bone marrow to hydrate her. “We failed,” Offit told me. “And then I was the one who had to go out to the waiting room to tell this mom of a little girl who had been previously healthy two days earlier that her child had died.”

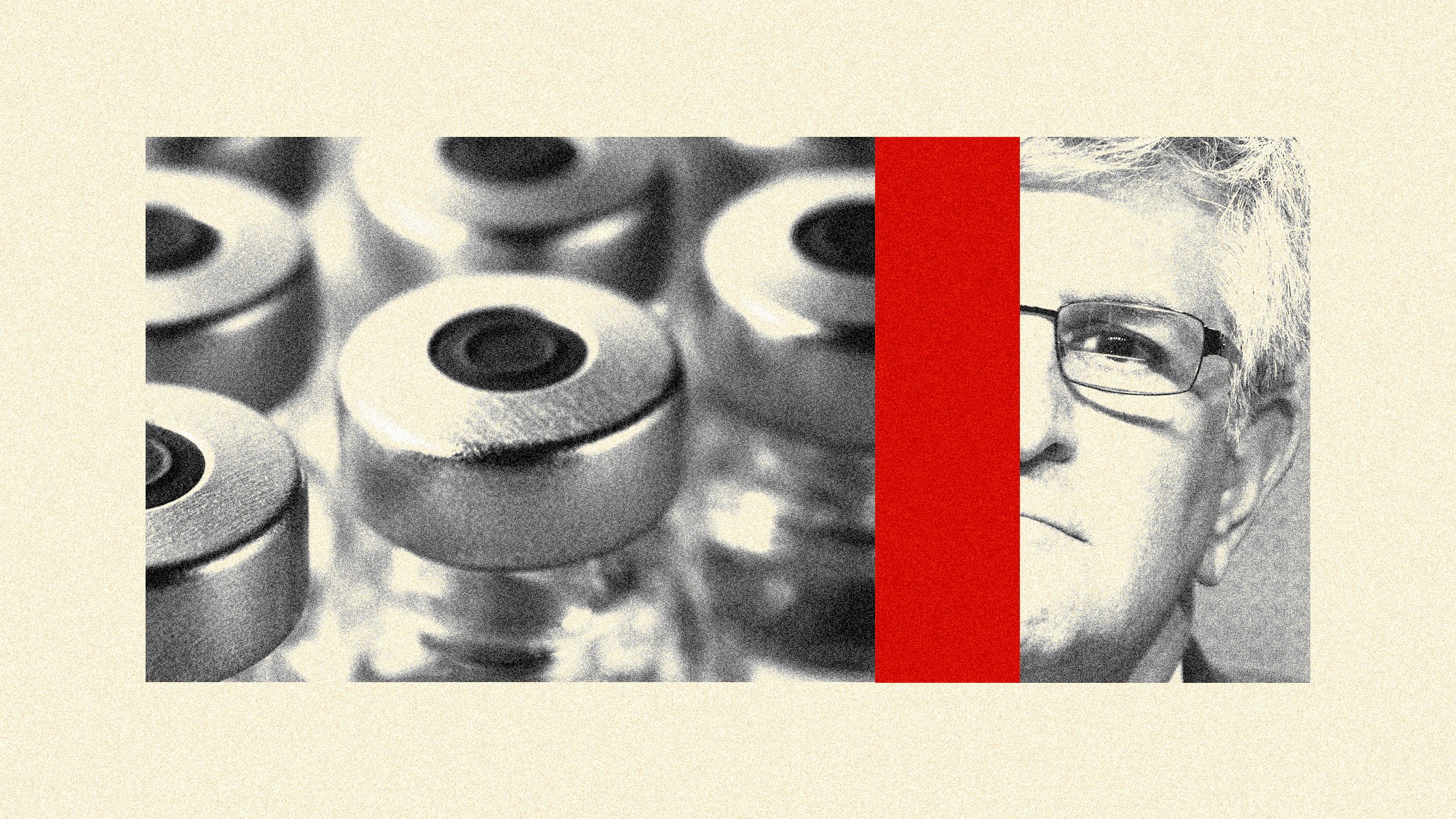

Within a few years, Offit had partnered with several other scientists and begun to develop a rotavirus vaccine. Their oral immunization, called RotaTeq and delivered as a series of sugar-sweet drops to infants, would ultimately be licensed in 2006. Today, it remains one of the two main rotavirus vaccines available to American children. Offit is now a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where, he told me, “most residents have never seen an inpatient with rotavirus-induced dehydration”—thanks in large part to the country’s deployment of rotavirus vaccines, which reaches about 70 percent of U.S. children each year.

Now, though, the United States’ rotavirus shield stands to fracture. Today, the Trump administration overhauled the nation’s childhood vaccination schedule, shrinking from 17 to 11 the number of immunizations it broadly recommends to all American kids. “After an exhaustive review of the evidence, we are aligning the U.S. childhood vaccine schedule with international consensus while strengthening transparency and informed consent,” Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy said in a statement today. Among the vaccines clipped—including immunizations against hepatitis A, meningitis, and influenza—is the rotavirus vaccine, which the administration frames as more of a personal choice, allowable under consultation with a health-care provider but not essential, because the virus poses “almost no risk of either mortality or chronic morbidity.” Experts suspect that vaccination rates will plummet in response. If they do, rates of diarrheal disease are likely to quickly roar back, Virginia Pitzer, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at Yale, told me. (The administration’s nod to international consensus is tenuous at best; rotavirus also remains the leading cause of diarrheal death among young children worldwide.)

In an email, Andrew Nixon, HHS’s deputy assistant secretary for media relations, defended today’s decision as “based on a rigorous review of evidence and gold standard science, not claims from individuals with a financial stake in maintaining universal recommendations.” (Offit, who is a co-patent holder on RotaTeq, did profit from his invention but sold his interest in the vaccine more than 15 years ago and does not currently receive royalties from its sale.)

I called Offit to discuss the federal backtracking on the vaccine he once helped bring to market, and what the loss of protection will mean for future generations. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Katherine J. Wu: Rotavirus was once a disease that hospitalized up to 70,000 children each year. Since the arrival of the vaccine you co-invented, as well as another two years later, those rates have plummeted. What was it like to see a vaccine you helped develop have that sort of impact?

Paul Offit: I remember a meeting at Merck [the company that manufactured the vaccine] when they revealed the results of our big Phase 3 trial. [The presenter] showed the data, that it clearly was safe, in 70,000 children. And it was like 95 percent effective at preventing severe illness. She showed a map of the world, with Asia, Africa, Latin America studded with black dots, and each black dot represented 1,000 deaths. She said, “Now we have in hand the technology to prevent this.” Then she showed a picture of a map of the world where all those black dots were gone. And she put her head down, shoulders going up and down, and wept.

The vaccine was taken up relatively quickly, I think in large part because it was an oral vaccine and that is perceived as less difficult than a child getting a shot. To go from 1980 to 2006, and to start to see the incidence of the disease decline, it was just an amazing feeling.

Wu: What will it mean for this vaccine to no longer be recommended by the federal government?

Offit: My wife’s in private practice in pediatrics, and there certainly were many parents who she saw who were hesitant about getting vaccines. And I think it’s more convincing when you can say, “Look, this is a recommended vaccine. This is something that the CDC, the major public-health agency in this country, believes is important for your child to receive.” You can’t really say that now. And if you get rotavirus in early childhood, you have a chance of being one of those 70,000 children [who were hospitalized] before there was a vaccine.

Some diseases, you need to build up a susceptible population, like measles, which we eliminated from this country. That’s not true for viruses like rotavirus, flu, RSV. The virus is always circulating. So if you choose not to get a vaccine, you are at risk, because you may come in contact with that virus. So if there’s a fairly rapid erosion in vaccine rates, I think you would immediately see children suffering a preventable illness.

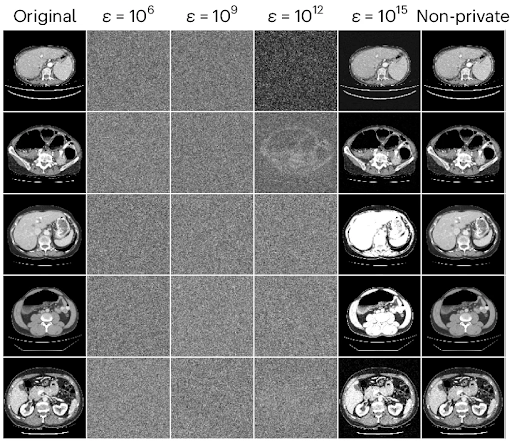

Wu: In a decision memo addressed to the acting director of the CDC, top officials at the Department of Health and Human Services downplayed the virus’s threat to American children and suggested that the decrease in rotavirus deaths that followed the approval of RotaTeq and another vaccine called Rotarix may instead have been attributable to factors “unrelated to the vaccine, including improved medical care, changes in diagnostic practices, or random fluctuations.” I’m curious what you make of that justification. Were there other reasons rotavirus might have been among the six vaccines targeted?

Offit: A phrase like almost no mortality—really? So the 20 to 60 children who died every year of rotavirus in this country, that’s okay? One child dying is too many, especially if you can safely prevent it. So I don’t agree with that.

Sure, right now the morbidity is low because of the vaccine, and certainly the mortality is largely gone because of the vaccine. We are once again exposing children unnecessarily to harm. There’s no advantage to this. There were 70,000 hospitalizations a year, which was not trivial, and virtually eliminating them was one of the major successes for vaccines in this country. And I don’t understand why you would ever back off that success.

I also just never imagined we would ever get to a time when the CDC, the nation’s No. 1 public-health agency, and the ACIP, which was a group of outside expert advisers who went through the science and made best recommendations, would get to the point where it was basically not a scientific organization anymore. It’s an organization run by an anti-vaccine activist who was a science denialist and conspiracy theorist. I mean, that’s where we are now. We don’t have the CDC anymore. We don’t have an ACIP anymore. I certainly never imagined that. [Editor’s note: Kennedy has an established history of anti-vaccine activism and of embracing conspiracy theories. Nixon, the HHS spokesperson, did not offer further comment on this criticism.]

Wu: This actually isn’t the first time that a rotavirus vaccine has lost a government endorsement. The U.S.’s first rotavirus vaccine, RotaShield, was taken off the market in 1999 after officials detected a rare intestinal-blockage complication. How does the current situation compare? Was there a safety reason to make current rotavirus vaccines less accessible to the public?

Offit: I was actually on the ACIP when that happened. [Editor’s note: Offit was no longer on the ACIP when his own vaccine was voted on.] The [rare side effect was] quickly picked up, and the vaccine was off the market within a little over a year. We care about vaccine safety. It depends on which paper you read, but anywhere from one in 10,000 to one in 30,000 children developed [the blockage]. You were still at greater risk of being hospitalized and dying from rotavirus, but the decision was made to take it off the market.

Wu: What do you think will be the future of the rotavirus vaccine you helped develop and bring to market, and watched help reshape the portrait of diarrheal disease in this country?

Offit: The American Academy of Pediatrics will certainly still recommend it. But younger pediatricians may be less compelled to offer this vaccine, because they didn’t experience this disease when they were in training. But I think what they hopefully realize is that this virus continues to circulate. It’s still out there. And the lower immunization rates, even a little, will cause children to suffer unnecessarily.